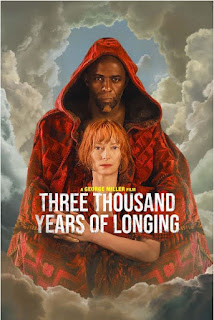

Not long ago, I got around to watching Three Thousand Years of Longing. (I admit it: I skipped the in-person theater experience and waited 'til the streaming price had dropped below ten bucks.) I had really looked forward to this film. It seemed promising: the stars are Tilda Swinton and Idris Elba, and it included some Arabian Nights-like tales.

And at first blush, the film delivered: it had humor and tenderness and love, and if not a totally happily-ever-after ending, then at least an as-happily-as-things-could-end ending. I came away from it oddly satisfied.

But as the glow faded, I started thinking about what I'd seen. And I came to the conclusion that I'd been had.

First, though, the premise: Swinton plays Alithea Binnie, a narratologist -- a scholar of storytelling. She is in Istanbul for a conference of like-minded scholars when she runs across a decorative bottle in a junk shop. Impulsively, she buys it. The next morning, as she's cleaning who knows how many eons of grime off the bottle, the top pops off and out swirls a djinn, played by Idris Elba. The djinn tells her he's been trapped in that bottle for a couple of centuries. Then he pesters her into making three wishes, as djinni do -- and they must be for her heart's desire. "I know what women want," he says at one point, or words to that effect. There must be something her heart desires.She shrugs. Her heart desires nothing. She is happy with her life in London and with her career. She had a love affair once that didn't work out, and now she is happy to be single. The only thing she wants is to know how the djinn got stuck in that bottle.

Thereby hangs the majority of the movie. The djinn recounts his adventures -- or rather, misadventures -- with several women, starting with the queen of Sheba and ending, always, with him trapped in a container of some sort for the next several hundred years.

His tales have an extraordinary effect on Alithea. She decides what she wants, more than anything, is to be loved the way this djinn had loved the queen of Sheba. And because his nature requires him to grant wishes, he does.

As Alithea observes, though, in any story involving the granting of wishes, there's always a catch. In this story, the transition for the djinn to the modern world nearly kills him -- so of course he and Alithea can't be together forever. They work out a sort of truce -- that's the as-happily-as-things-could-end ending I mentioned earlier.

I don't think I'm spoiling much by telling you all this. The published reviews I've seen cover the same points -- and as most of those reviewers have said, the best parts of the movie are the stories the djinn tells. Once he has granted Alithea's wish, he stops telling stories, and the rest of the movie kind of flits by.

But as I've said, I liked it when I saw it. I liked that things didn't work out perfectly for Alithea and the djinn; that's how love affairs typically go, even when they don't involve a magical creature. My problems began later, after I thought about what I'd seen.

My main issue was that the djinn never explained what he meant when he said he knew what women want. And after ruminating on it, I realized that what he may have meant is this: No matter what a woman says -- no matter how happy she claims to be -- her heart's desire is to be loved and cherished by a mate.

And here I thought the heart's desire of all women was to have functional pockets.

No, really. Many of us are perfectly happy alone. The implication that when we declare that happiness, we are lying to ourselves -- that we doth protest too much -- is an insult.

But that never occurs to Alithea when she jumps from "I'm happy with my life the way it is" to "love me like you loved the queen of Sheba." I get that the movie is supposed to be a love story, but come on.

The film has other problems, implicit racism being one of them. But this was the thing that bugged me the most.

If you've seen it, let me know what you thought.

***

I still maintain that the thing women most wish for is functional pockets.

***

These moments of wishful blogginess have been brought to you, as a public service, by Lynne Cantwell. Stay safe!

5 comments:

This is Mary…I gave up romance films years ago because they never start with the man being happy then along comes a woman. It’s the perpetual concept that women are not complete without a man…

Thank you for saving me money. Now I don’t have to watch it. And you’re right, that’s dumb. What’s even dumber is that she didn’t make him explain that statement and challenge him.

I haven't seen it but what you say bothers me, too. It's the idea that MEN know what women want, so that makes them superior to us and in a position to make decisions for us. Typical patriarchal view and one that prevails still. Grrr.

Hmmm. Are the two ideals mutually exclusive ? I mean, does accepting the idea that a woman can live a complete and fulfilling life on her own necessarily preclude the idea that having a loving (male or female) life partner would be a wonderful thing?

In response to whether the two are mutually exclusive: There's a whole lot of loaded language in your question. :D The issue here is not whether a "loving...life partner would be a wonderful thing"; it's that for decades and perhaps centuries, women have been sold the idea that they can't possibly be happy *without* having such a partner. Women who haven't been lucky enough to find one -- and yes, luck *is* involved -- are considered in many respects to be "less than", even by the woman herself. Then the self-loathing kicks in. Not to mention the pressure from family, society, and even oneself to stick with a relationship that's in no way ideal, because then at least the woman won't be alone.

I'm not saying great relationships don't exist. I'm saying it's a mistake to tell women they can't possibly be happy without one, and they're lying to themselves if they think they are. That's what this movie does.

Post a Comment